‘Surviving A Brandalism Attack’ – Ex Google & Apple Lawyers Publish Legal Advice for Corporations

27 Jan 2018

– ‘How To Survive A Brandalism Attack’ –

Ex Google & Apple Lawyers Publish Legal Advice For Corporations

Words by Bill Posters.

Intro

On the 1st of January 2015, a curious legal paper appeared in Volume 10 of the Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice entitled ‘Brandalism & Subvertising – Hoisting Brands with their own petard?’ (what this actually means we will get to later). Within its pages, two lawyers – one ex-Google, one ex-Apple had taken the time to – or rather – had been paid to prepare a legal paper that surveyed international court cases, as they sought to inform multinational corporations of their chances of success if they ever decide to prosecute Brandalism (and others), for our art.

To our knowledge (and please email us to correct us if we are wrong), this is the first time that an art project has provoked a legal response of this nature from large scale multinational corporations. What is clear is the fact that lawyers for large scale corporations believe that ‘Brandalism is changing the marketing landscape for many brand owners’, for in their own words ‘there is now a significant risk that brand owners’ expensive advertising campaigns could be hijacked and distorted’. What isn’t immediately clear at this moment, is which company – legal or otherwise, paid these expensive lawyers for their time to write this paper.

To explore this we must first provide a little background on the paper’s authors. Adam Smith-Anthony was previously employed by Google and now works for Omnia Strategy – the same legal corporation as Cherie Blair CBE, the unfortunate spouse of Tony, remember? The massive knob that illegally took the UK to war in Iraq in 2001.

According to Omnia Strategy’s website, they are ‘a pioneering international law firm that provides strategic counsel to governments, corporates & private clients’. The second author of the paper is John Groom, an Intellectual Property rights lawyer working for Baker Mackenzie – one of the world’s most profitable legal corporations with reveues in excess of $2 Billion in 2015. According to their latest marketing video, they are the ‘New Lawyers for the New World’ helping people who can afford it to find ‘clarity within chaos’. This evokes visions of lots of middle aged white, privileged males, bureaucratically carving up every aspect of human existence into neatly folded piles of chino-like remorse. Dutty.

Brandalism and subvertising: hoisting brands with their own petard?

So what does this legal paper actually mean for subvertisers? Before that, perhaps we should start with trying to figure out what this title actually means because this latter point will have an impact on the former. Who in the world even knows what a petard is?! Who speaks this metaphorical shit? The 1% it appears. We had to google this to find out what it means, as I’m pretty sure everyone at Brandalism HQ has never hoisted anyone’s petard, but we can’t be sure, things get messy sometimes. So… just for clarity, and to debunk the millions of euphamisms that this strange phrase emotes, here is a telling definition.

To even begin to grasp meaning we need to take a journey back in time to oxford in the 1600s, where we can see William Shakespeare, like a living cliche, quill in hand, about to write Hamlet. In the process he is creating the insanely bizarre phrase to ‘hoist by one’s own petard’ as a metaphor for explaining about some dude that wanted to kill a dude but then the same dude gets killed by another dude’s dude. A double negative dude if you will.

So what does this actually mean and who are all these dudes?

Forget the dudes.

The term hoisted by one’s own petard means to fall foul of your own deceit or fall into your own trap. This term has its origin in medieval times when a military commander would send forward one of his engineers with a cast-iron container full of gunpowder, called a petard, to blow up a castle gate, obstacle, or bridge. The fuses on these bombs were very unreliable, and sometimes the engineers (of consent in the context of advertising) would be killed when the petards exploded prematurely. The explosion would blow (or hoist) the engineer into the air.

Interesting. So why am I still writing about it? For what reason is it important – and not just for lawyers who want to show off about how much shakespeare they can regurgitate on command for their overlords?

What the lawyers were trying to so eloquently explain is that multinational brands are vulnerable. In a globalised, neoliberal market place, perception is everything, in fact most of a multinational brand’s value is perceived. A brand’s value isn’t just down to the physical tangible (material) assets that a corporation owns, its also valued by the way others see it, valued by what it signifies to whom – it’s ‘brand capital’.

Considerations for Subvertisers

So whilst multinational corporations pay the world’s most expensive psychologists, creatives and celebrities to blow up the bridge or castle gate to your mind with their slick advertising campaigns designed to create perceptions of value and need, subvertisers on the other hand can blow up the engineers of consent, before their well architectured communications reach your mind’s gate, bridge or whatever. This is the potential power of subvertising and corporations know it. They know it enough to pay two lawyers from two of the world’s leading law firms to tell other corporations what they can legally do to protect themselves and their brand’s ‘perceived value’.

It’s worth pointing out here that the etymology of the word ‘petard’ is French and it means ‘break wind’, so we could also argue that the authors of this legal paper are literally , metaphorically and actually talking shit. But we won’t, because we’re bigger than that, just.

In the introduction of the legal paper, the authors state that:

‘In considering how brandowners might respond to such brandalism campaigns, the article will consider: the extent to which intellectual property rights can be said to be infringed by such activity; the impact of parody defences in Europe and the parameters of fair dealing; the practical/commercial factors to be borne in mind; the relevance (and threats) of social media and viral memes; and the role (if any) of criminal enforcement.’

So it looks like the lawyers are focussed on accertaining two crucial things. Firstly how scared they are by social media impacts of subvertising, secondly whether they can even take legal action against Brandalism without damaging their brand’s ‘perceived value’. It wouldn’t look too cool if a hip, trendy major international brand started legal action on some undeground, ‘cool’ subversive artists now would it? Not when they have some of world’s most prominent artists in their corner (shout out to all our artists!).

Perhaps this is the reason why after our first Brandalism project in 2012 when we managed to call out the Chief Exec of the Outdoor Media Centre who promised to ‘squash’ us as quick as possible (Hmmm not quite Mike Baker), the entire ad industry would refuse to comment to any press journalists about our subsequent projects. Basically their strategy was to remove the media oxygen from the press bonfire in an attempt to ‘return to normal’ as quickly as possible. The reason why? This is basically the only tactic they can use in their defence. Their own legal advice below shows it. Take a look at the ‘chief exec’s checklist’ proposed towards the end of the paper to see how concerned multinational brands are.

The question then for subvertisers, activists and campaigners, is how can we exploit, how can we hack this weakness of multinations corporations?

Here’s the legal paper in full, its a fascinating read (you can also download a pdf version from our ‘Take Action’ page here) and will no doubt arm subvertisers around the world with the knowledge and confidence that their art and their actions are having a direct impact…

Brandalism and subvertising: hoisting brands with their own petard?

Abstract

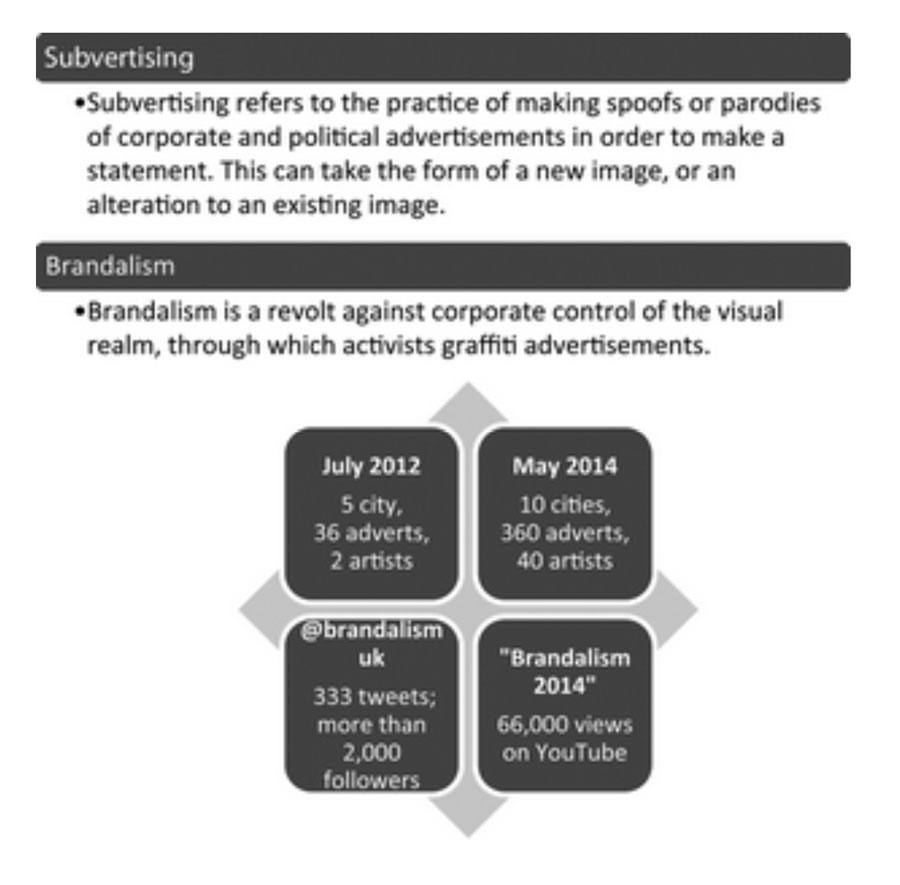

Brandalism is a movement with the stated aim of rebelling ‘against the visual assault of media giants and advertising moguls who have a stranglehold over messages and meaning in our public spaces’. Through public acts of ‘subvertising’, where through spoofs, parodies and other message-changing/obscuring alterations, activists seek to use a brand’s own marketing channels to make a statement against the brand itself. Subvertising typically involves artwork commenting on consumerism, cultural values, debt, the environment, body image or specific political messages placed over existing billboards at bus stops and other public spaces.

The article will identify the recent rise of brandalism, referring to examples from spring/summer 2014. It will also analyse the movement and its possible impact against the backdrop of on-going discussions relating to the appropriate balance between, on the one hand, brand owners’ intellectual property rights and protections against defamation, and, on the other, the free expression rights of individuals and other groups.

The article will draw on cases where courts in Europe have considered such issues and ruled where the balance between these conflicting sets of rights should lie. In considering how brandowners might respond to such brandalism campaigns, the article will consider: the extent to which intellectual property rights can be said to be infringed by such activity; the impact of parody defences in Europe and the parameters of fair dealing; the practical/commercial factors to be borne in mind; the relevance (and threats) of social media and viral memes; and the role (if any) of criminal enforcement.

The Authors

Adam Smith-Anthony is a Senior Associate at Omnia Strategy LLP and John Groom is an Associate at Baker & McKenzie LLP. They are grateful to Ben Allgrove of Baker & McKenzie LLP for his input.

This article

– Brandalism is a movement with the stated aim of rebelling ‘against the visual assault of media giants and advertising moguls who have a stranglehold over messages and meaning in our public spaces’. Through public acts of ‘subvertising’, where through spoofs, parodies and other message-changing/obscuring alterations, activists seek to use a brand’s own marketing channels to make a statement against the brand itself. Subvertising typically involves artwork commenting on consumerism, cultural values, debt, the environment, body image or specific political messages placed over existing billboards at bus stops and other public spaces.

– The article will identify the recent rise of brandalism, referring to examples from spring/summer 2014. It will also analyse the movement and its possible impact against the backdrop of on-going discussions relating to the appropriate balance between, on the one hand, brand owners? intellectual property rights and protections against defamation, and, on the other, the free expression rights of individuals and other groups.

– The article will draw on cases where courts in Europe have set out where conflicting sets of rights should lie. In considering how brandowners might respond to such brandalism campaigns, the article will consider: the extent to which intellectual property rights can be said to be infringed by such activity; the impact of parody defences in Europe and the parameters of fair dealing; the practical/commercial factors to be borne in mind; the relevance (and threats) of social media and viral memes; and the role (if any) of criminal enforcement.

… Trademarks, intellectual property rights and copyright law mean advertisers can say what they like wherever they like with total impunity. F[—] that. Any advert in a public space that gives you no choice whether you see it or not is yours. It’s yours to take, re-arrange and re-use. You can do whatever you like with it. Asking for permission is like asking to keep a rock someone just threw at your head. …

– Banksy / Tejaratchi

The Banksy epigraph above, while clearly not an accurate summary of brand owners’ motivations, shows that there is a powerful threat to their advertising campaigns. That threat was realized on a national scale in May 2014, when a group of anonymous artists and activists (or, to use the lingo, ‘subvertisers’) carried out an extensive campaign in the name of ‘brandalism’. Over two days, they doctored or replaced large commercial and political billboards and other roadside advertisements. Banksy’s words epitomize the motivations of those behind the movement. Their exploits gained prominence among the blogging community, attention on YouTube and even coverage in national newspapers, at the financial and commercial expense of brand owners.

In this article, we explore the motivations behind the brandalism movement and consider its effects on brand owners’ IP and commercial interests. We review the traditional legal tools available to rights holders and others targeted by these counter-culture guerrilla attacks, but look too at the strengthening of protections of expressive freedoms, exemplified by the introduction of parody as a defence in copyright law and demonstrated by judicial pronouncements applying Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). We conclude with a check-list of factors for business executives, in-house counsel and external advisers to bear in mind when reacting to a brandalism attack, and we sound a cautionary note that practical and reputational issues may militate against ‘going legal’ and require instead a more creative response.

What is brandalism?

The concepts of brandalism and subvertising are not new and to some extent ‘culture jamming’ issues and methods dating back to the 1950s were relabelled as brandalism in May 2014 when street artists subvertised 360 corporate advertising spaces across ten cities in two days; original artwork was supplied by 40 international artists for the campaign, including internationally recognised artists. Artworks were shared via the twitter handle @brandalismuk.

The stated aim of today’s brandalism movement is to rebel ‘against the visual assault of media giants and advertising moguls who have a stranglehold over messages and meaning in our public spaces’. Through public acts of ‘subvertising’, spoofs, parodies and other message-changing or obscuring alterations, activists seek to use brands’ own marketing channels to make a statement against the brands themselves. The movement represents a backlash against the perceived ubiquity and dangers of modern corporate advertising. Subvertising typically involves artwork commenting on consumerism, cultural values, debt, the environment, body image or specific political messages placed over existing billboards at bus stops and other public spaces.

Examples in the ‘real world’ (ie offline) include a replaced bus stop advertisement outside Harrods that, under the sobriquet ‘Horrids’ (styled to resemble the Harrods mark), bemoaning the ‘cluster bombs of consumerism’, and 200 ‘Gatwick Obviously’ posters defaced or replaced by the Plane Stupid environmental pressure group. In the political sphere, the UK Independence Party’s campaign ahead of the May 2014 European Parliament elections was targeted, with billboard adverts defaced with graffiti or painted entirely grey.

However, it is not the physical graffiti on the high street that poses the greatest threat to brand owners; it is the potential of social media to create a forum for images of brandalized adverts to be shared over and over again that is most worrying to brands. Having your quirky advert go viral is a standard marketing objective; facing a defaced version of your advert plastered across the internet is another matter entirely. Compare the legion of online spin-o s of both WATERisLIFE’s ‘first world problems’ campaign and MasterCard’s ‘for everything else there’s MasterCard’ ads, which served to reinforce and amplify the original message, with the 2012 Nike advert featuring Wayne Rooney, doctored to show Footlocker and JD Sports bags dangling from the footballer’s outstretched arms and with the famous trade mark ‘Just Do It’ changed to ‘Just Loot It’, or the UK Conservative Party’s 2010 ‘Year for Change’ election posters, which prompted a huge run of ‘Airbrushed for Change’ spoofs and even a ‘make your own David Cameron poster’ website: brandalism en masse.

Brandalism is changing the marketing landscape for many brand owners: there is now a significant risk that brand owners’ expensive advertising campaigns could be hijacked and distorted—whether by organized brandalists or by individuals adding to a meme—shared on social media, and ultimately showcased more than the original ‘on message’ campaign ever was.

Taking action: traditional legal tools

Copyright infringement

Could brand owners pursue a remedy as a result of copyright infringement if one of their billboards was doctored (in a similar way to the Nike/Rooney example above)? Copyright may subsist in various elements of the advert, including images, logos, or even the whole advert, depending on the facts. The ‘substantial part’ test likely will be satisfied in most cases because by their very nature these parodies are intended to look like and be recognised as the same or very similar to the original works. Any sort of copying or adaptation of the work may therefore amount to copyright infringement, as well, possibly, as derogatory treatment in violation of the authors’ moral rights.

Brand owners must also anticipate various defences available to their brandalist foe. The UK Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 (CPDA), for example, expressly permits fair dealing with a copyright work for the purposes of criticism or review, or reporting current events. Unhelpfully for brand owners, the courts have ruled that these expressions are of ‘wide and indefinite scope’ and to be interpreted liberally, and that fair dealing is an ‘elusive concept’ assessed as a question of fact and impression. What is clear is that fair dealing does not depend on whether a defendant’s criticism of a work is substantively justified (which Brandalism is),[missing text here] circumstances in which the old (but preserved) common law defence of public interest might override copyright have been described judicially as ‘probably not capable of precise categorisation or definition’. None of this will be much comfort to brand owners who, while perhaps unsympathetic to such arguments, remain keen to avoid public courtroom submissions on the relative societal merits of their businesses and the brandalists’ anti-consumerism critique-by-spray-can. This is a significant practical bar to bringing even a strong infringement claim. The same is true for Article 10 defences to copyright infringement, which we consider below.

Trade mark infringement

The judicial expansion of trade mark functions makes it easier to see how a claim for infringement could be made out, as pieces of brandalism more plausibly impact on the ‘investment function’ of a mark than bring into question the origin of the original work. It should be clear, for example, that Nike did not really launch an advertising campaign based on the theme of looting. For the same reason, infringement analyses will likely steer clear of parts 10(2) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (TMA) and its need to show confusion on the part of the public, and gravitate instead towards ‘unfair advantage’ or ‘detriment’ arguments under s 10(3).

However, one would still need to demonstrate use in the course of trade, which may be di cult on the facts. Might the brandalist also turn to s 10(6) TMA to assert legitimate use of the marks? This is unlikely to be persuasive in most cases, as the article is concerned with the use of marks to identify, in a manner conforming with honest trade practices, the undertaking responsible for goods or services. That said, could a defendant theoretically turn to free speech arguments to establish ‘due cause’—under either s 10(3) or s 10(6)—and avoid a finding of infringement? The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has previously held that fair competition is due cause,5 and given the increasing power of rights-based arguments under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), a free speech or parody defence may also be plausible, as we consider below.

Defamation

If the brandalist’s message defames a company or individuals, brand owners could potentially bring an action for defamation against the artist. The Defamation Act 2013 has been enacted to make defamation law more applicable to the internet age, and will be of interest to brand owners. The Act attempts to rebalance the focus of defamation claims from intermediaries, who gained a statutory defence akin to the safe harbour provisions found in copyright regimes, to the actual uploaders of defamatory statements. While at first blush the act is positive for brand owners, defamation requires ‘serious harm’ (ie ‘serious financial loss’) to be made out, which is perhaps too high a hurdle to clear in cases of defaced or repurposed advertising. Moreover, the Act puts the defences of truth, honest opinion and publishing on matters of public interest (formerly common law ‘Reynolds privilege’6) on a statutory footing, and do brand owners really want public discussion of arguments about the merits of criticisms levelled against them? For these reasons, plus the same reputational risks of perceived heavy-handedness noted above, defamation claims are not for the faint-hearted and should usually be viewed as the nuclear option.

Criminal

There may have been criminal activity involved with grafting posters or online brandalism, depending on the facts in each case. However, a brand owner may face difficulties getting engagement from the police and crown prosecution service in any given case. Further, there could be a large reputational risk to brand owners of involving enforcement authorities. When presented with the image of the big, ‘nasty’ brand owner mobilizing its resources (and harnessing those of the state) against a plucky brandalizer, there is a real likelihood that the public will turn against the brand owner.

Brand owners should, therefore, think carefully before pursuing criminal charges against offenders.

Removal, notice and takedown

From a practical perspective, the brand owner may be satisfied just to get rid of the o ending content, whether appearing on a bus shelter or online. In the physical world, this should be straightforward, although brands may want to consider service level agreements covering the speed with which their advertising partners get the offending copy removed and the original advert reinstated.

Online, the notice and takedown procedure is the brand owner’s friend. Depending on the platform, notice and takedown procedures can provide a relatively quick and painless means of removing identified content amounting to an infringement. However, this approach does not tackle the root of the problem, since the user generally can simply re-upload the content elsewhere (and perhaps complain about corporate censorship or otherwise make life more difficult for the brand owner).

Looking ahead to new developments

New parody exception

Until recently there was neither a fair use defence in the UK nor a parody exception in copyright law. However, a new copyright exception for ‘caricature, parody or pastiche’ came into force in the UK on 1 October 2014. The new exception seeks to protect imitations of copyright works for humour or satire and ‘give people in the UK’s creative industries greater freedom to use others’ works for parody purposes’. The government’s guidance advises:

The law is changing to allow people to use limited amounts of another’s material without the owner’s permission (new section 30A CDPA 1988). For example: a comedian may use a few lines from a film or song for a parody sketch; a cartoonist may reference a well known artwork or illustration for a caricature; an artist may use small fragments from a range of films to compose a larger pastiche artwork.

Clearly, this is a step towards greater protection of expressive freedoms, but what is the scope of this exception and to what extent might it make it harder to enforce rights against those misappropriating and adapting your copyright works to criticize your brand? The government has suggested that, to stay within the new defence, only a limited, moderate amount of a work can be used, and perhaps the courts will be conservative at first in their applicable of the law. Also, the courts will likely borrow from extensive jurisprudence on what constitutes fair dealing in copyright works (for example, in the criticism and review line of cases we touched upon above), rendering the parody defence less uncertain and worrying to brand owners than might initially seem the case.

Some commentators have suggested that trade mark law should follow suit and introduce parody as an example of permitted ‘honest referential use’ of a mark, alongside use for the purposes of indicating replacement or service, or for commentary and criticism.8 It is not clear that, in the UK context, this would add much to the existing s 10(6) defence, considered above, or the extent to which such a development might prove unnecessary should the British courts follow their continental counterparts in recognising in parodies a human rights defence to IP infringement.

ECHR arguments

The UK Human Rights Act 1998 requires a court determining a question that has arisen in connection with an ECHR right to ‘take into account’ any relevant jurisprudence from Strasbourg, and to not act in a way that is incompatible with an ECHR right. To appreciate what the courts must be mindful of, we turn to rulings on the scope of these ECHR rights, including those from other ECHR member countries.

In 2013, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) clarified, ‘[f]or the first time in a judgment on the merits’, that a sanction or other judicial order for copyright infringement can be regarded as an interference with ECHR. In this case, three photographers in France published unauthorised catwalk photographs on a fashion website and were convicted of copyright infringement. The ECtHR held that the photographers’ free speech rights had not been infringed; however, the court reasoned that the publication of the photographs had been purely commercial and had not contributed to any important topic of public debate. Would an overtly satirical and non-commercial act of brandalism tip this balancing exercise between the right of freedom of expression and a copyright owner’s IP rights the other way?

In 2005, the German Federal Court considered whether postcards which mocked trade marks and advertising campaigns of the chocolate producer Milka amounted to trade mark infringement. The defendant had used Milka’s abstract purple colour mark as a background colour for the postcards, inscribed with language ridiculing the idyllic countryside scene used in Milka’s advertising campaigns. The court held that it was sufficient that the postcard simply called to mind the well-known Milka signs, in order to qualify as ‘use’. The court also considered whether the postcards were detrimental to distinctive character or repute, and whether they had taken unfair advantage of Milka’s marks. The court found that there had been trade mark infringement; however, it weighed those concerns about disparagement of Milka’s marks against the fundamental guarantee of the artist’s freedom of expression. The court concluded that the artist’s freedom of expression had to prevail in light of the ironic statement and parody made with the postcard. The defendant therefore could rely on the defence of ‘due cause’ in respect of the parody. This is just one example —there have been many more cases where ECHR arguments have trumped IP rights.

Even where a finding of infringement is made, free speech arguments may resurface when considering the appropriateness of remedies. Mr Justice Briggs, in a High Court judgment in 2013, noted how it is ‘in theory possible that the propensity of an injunction restraining a threatened breach of copyright to impinge upon a defendant’s Article 10 right to freedom of expression might occasionally incline the court, on particular facts, to decline the discretionary remedy of an injunction, and leave the claimant to claim in damages’. So, even where the brand owner defeats an ECHR defence to infringement, Article 10 concerns may still deprive it of its most impactful remedy.

Is it worth taking action?

As we have alluded to above, when faced with a brandalism attack, establishing a cause of action is only one of the factors to take into account when deciding how—or whether—to respond. A plethora of practical and commercial considerations means that taking time to carefully assess the situation and options, as well as the brand’s objectives, will be more prudent than rushing to fire off a cease and desist letter or file a claim at court.

In 2012, when Hillary Clinton was US Secretary of State, a photograph of her sending a text message went viral, with users adding their own words for the text—a kind of unsolicited caption competition played out spontaneously on social media. A dedicated blog was set up showing different user-generated takes on the meme, and the pictures trended under the hashtag #tweetsfromhillary. While many of the posts were favourable, the situation was potentially embarrassing but was both harnessed and diffused when Clinton invited the two bloggers behind the meme to her office and initiated a photograph of all three texting on their phones. According to CNN, not only was the blog shuttered within a week because the meeting with Clinton could not be topped, but also Clinton’s image was ‘altered almost overnight’ from a serious veteran on the political scene to a humanized person and brand able to laugh at herself.

Go Compare, the online financial services company, provides another case study. Perhaps by design, the brand’s marketing lacked the public goodwill that Clinton was able to tap into; its TV adverts, featuring a curiously annoying character was widely reported online as irritating and managed to take the top two spots in the Advertising Standards Authority’s top ten most complained about adverts of 2013. Examples of defaced Go Compare billboard adverts have appeared online, including one featuring expletives and phallic symbols. To maximize exposure, Go Compare released a new billboard campaign bearing seemingly vandalized versions of its own posters: in classic spray-paint style, ‘Go compare’ was obscured and replaced with ‘go and get some singing lessons’, ‘go jump o a cli ’ and ‘go get a new job’. The brand’s messaging was coordinated; a spokesman declared how ‘Gio is very important to us, but we realise there are some people that don’t love him in quite the same way that we do … it is a fun campaign and, as the reaction on Twitter shows, that’s exactly how people are responding to it.’ In this case, embracing the brandalism seems to have obtained better results for the brand than would have been the case if they had tried to fight it.

Here is a checklist of issues for brand executives, in-house counsel and external advisors to be mindful of when making this assessment:

- Do you want to be proactive, and track brandalism websites and notorious twitter handles, or reactive, picking up on issues when you realize they have gained traction?

- What does your team think of the brandalism attack? Does it raise new concerns or draw attention to existing criticisms? Has it reached an audience beyond the core Brandalism movement? Is it gaining momentum amongst users online or in established media channels? Objectively, is it harmful or just irritating (noting that some studies have claimed that parody can actually be beneficial to the brand, through increased publicity and awareness)?

- What are your objectives? Do you want to remove the o ending material, set the record straight, improve the brand image, maximize publicity, apologize for any failings that have been exposed?

- Can you work through the intermediary, eg removal of defaced billboards by the advertising company or follow notice and takedown procedures of hosting sites online? Is an injunction required to force the intermediary’s hand? Will this solve or just redirect the problem?

- Who is the culprit? Can you identify the individual(s) responsible?

- Consider whether a combative response is commercially practical and the potential negative backlash to a perceived heavy-handed response, eg involving the police or filing a defamation suit. Beware of adding fuel to the fire.

- Has your IP been infringed? Do you need further advice on the merits and strength of your case? Can you evidence your rights, eg can you demonstrate ownership of any copyright works, designs or marks you would want to rely on, based on IPR records?

- Can the would-be defendant rely on fair use and/or human rights defences?

- Can you internally address any criticisms raised, eg rectifying poor customer experience, inferior product quality, or supply chain non-compliance? Would such a review take the heat out of the situation and ultimately improve your business?

- Is there scope for a more creative response? If you can?t beat them, can you join them?

To cherish in time?

Brandalism may well be a huge annoyance to brand executives who see their corporate message hijacked. In-house counsel and external advisers may find themselves pressured to act in a fast and firm manner, given embarrassment and perhaps anger at executive or board level. There are certainly legal tools that can be evaluated; however, there are clear signs which should give brands pause for thought. The general development in recent years towards elevating citizens? rights around social commentary and parody above the intellectual property rights that are subject to them puts brand owners in a difficult legal position. Beyond the legal strictures, there are likely enormous practical difficulties in securing a remedy and is, above all, a real risk that ill-conceived or knee-jerk responses will only make the situation worse.

In many cases, the best response may, therefore, be non-legal. Perhaps real concerns are identified which should be addressed internally, or perhaps the best approach is to do nothing at all? Or just maybe the brand might find that a well-judged contribution to the public discourse might actually enhance the standing of the brand or otherwise achieve its objectives. Or maybe the brandalism is an original Banksy, and you will learn to cherish it in time.

To view the source version of this paper click here