Debt

Debt

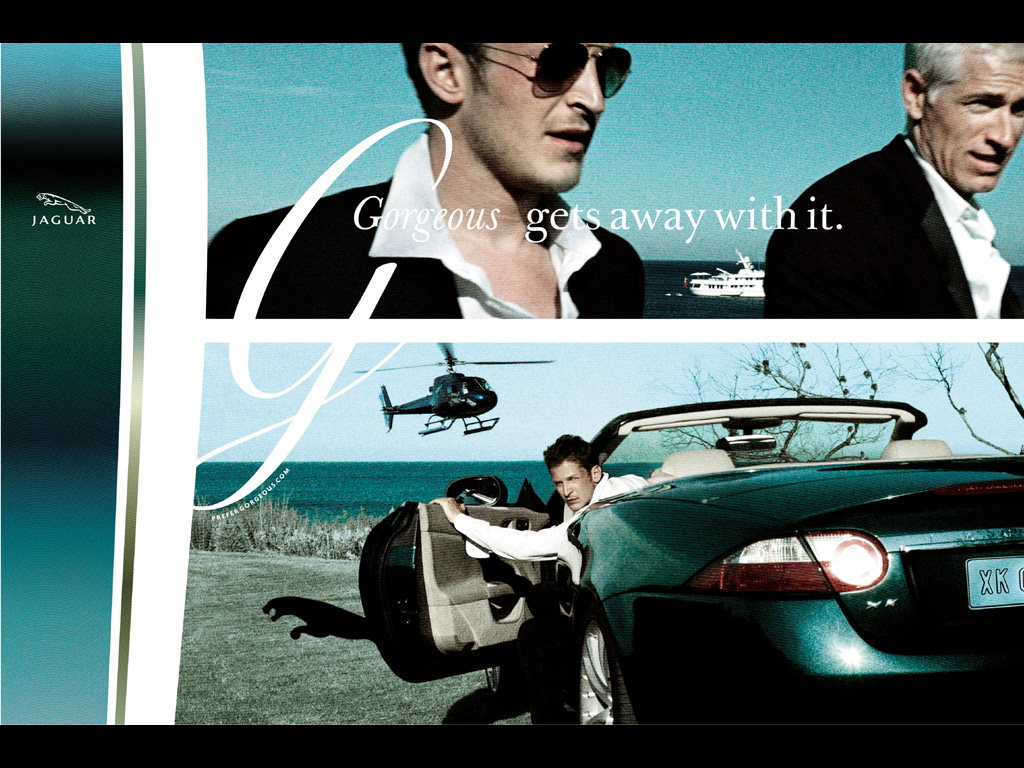

‘Everyone cares what gorgeous says’, ‘Gorgeous trumps everything’, ‘Gorgeous pays for itself’, ‘Gorgeous is worth it’ proclaims the now infamous Jaguar commercial, while attractive young women and wealthy ‘older gentlemen’ enter and leave exclusive hotels, parties and bars.

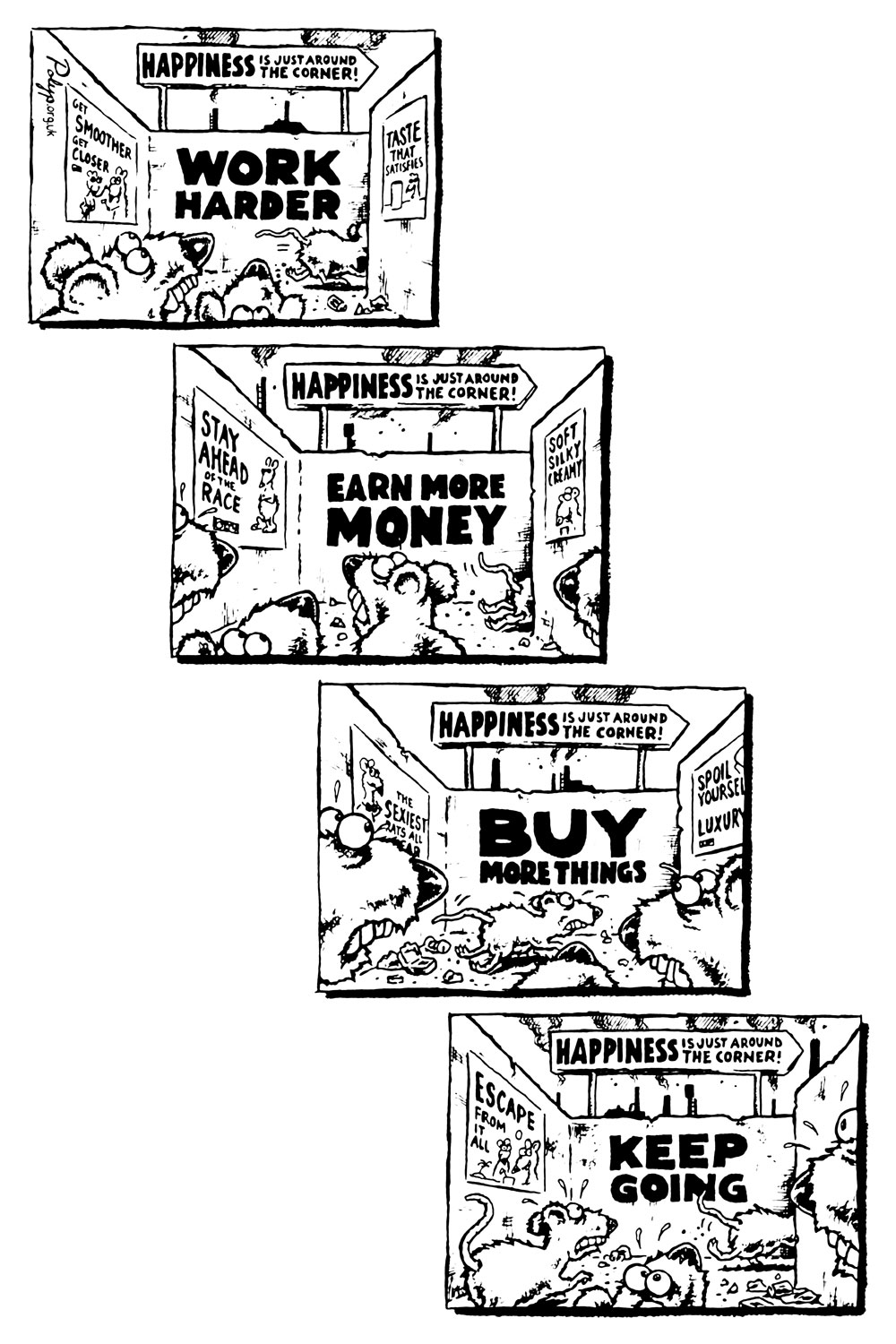

Most people probably won’t get into debt to buy a Jaguar – often it is purchases of more trivial things like clothes and shoes that lead people gradually to creep into greater debt and sometimes it is the basics like rent and food that drive people to borrow more. But this advert is synonymous with the idea that excessive consumption is normal – that although these cars are out of the reach of all but the wealthiest aspiring to purchase them is a commendable aim. To pay for our increasingly lavish consumer lifestyle there are two options: work harder and longer, or borrow. We are doing both. Driven by the pressure placed on us to continue spending and the desires created through advertising many of us have chosen to borrow to supplement our wages, which despite working longer hours for many have decreased in real terms.

Artist: Polyp (UK), Brandalism, 2014

In the UK as individuals we now owe a collective £1.3 trillion on credit cards, store cards, mortgages and loans. This figure is around 140 per cent of household income and has increased dramatically over the last decade; it stood at 105 per cent just ten years ago.

Our total individual borrowing is equivalent to a third of the UK’s total GDP, which in 2008 stood at £3.1 trillion. Financially vulnerable individuals are increasingly encouraged to take out unsecured personal debt and as a result we have seen an increase in low-income individuals accessing unsecured debt in the form of credit cards, store cards and personal loans. These often come with harsh penalties for missed payments and high interest rates. In 2008, at the peak of the crash, Argos was offering a store card with a 222 per cent interest rate. The card, which allows you to spend between £300 and £500, was advertised as being a good way to keep a check on what you spend – but most customers surely wouldn’t realise that £300 repaid in £9 payments over 56 weeks becomes £504 in interest alone. Low income households with debt have the highest level of debt in relation to their income, meaning that their financial insecurity is much greater than those even slightly up the ladder, and this has got worse over the last decade.

Artist: Peter Kennard, Brandalism 2012

Most people are home owners – about 70 per cent of people own their own homes. These people have an asset which in many cases is larger than the value of their debt, both unsecured and secured, and in a recent survey 40 per cent of householders agreed with the statement: ‘My house value has risen so much that I do not worry about other debts I may have.’

With house prices – which have acted as an illusory cushion for other financial problems – now in an unstable state – secured and unsecured debt are likely to become an increasing problem.

We are already seeing the result of this in the form of higher bankruptcy rates: in 2005, before the crisis started, 67,584 declared bankruptcy; by 2008 this figure had risen to 106,544, if it wasn’t for significant government intervention this number would be even higher.

This level of debt is bad not just for individuals but for economic stability, as the root of the current financial crisis has been traced to the collapse of the sub-prime market and easy credit. But debt is crucial to turning the ever faster wheels of our consumer society; it is the West’s dirty secret as individuals have been encouraged – often by day-time TV adverts – to take out more and more debt to live the life as advertised.

Adapted from ‘The Advertising Effect‘ by Compass (2009).