Subvertising – Art as Activism: 3 Interviews, 3 Perspectives

26 Feb 2017

Subvertising – Art as Activism

Vyvian Raoul brings us three exclusive interviews with the subvertising artists featured in a new book on the contemporary subvertising movement entitled ‘Advertising Shits In Your Head’.

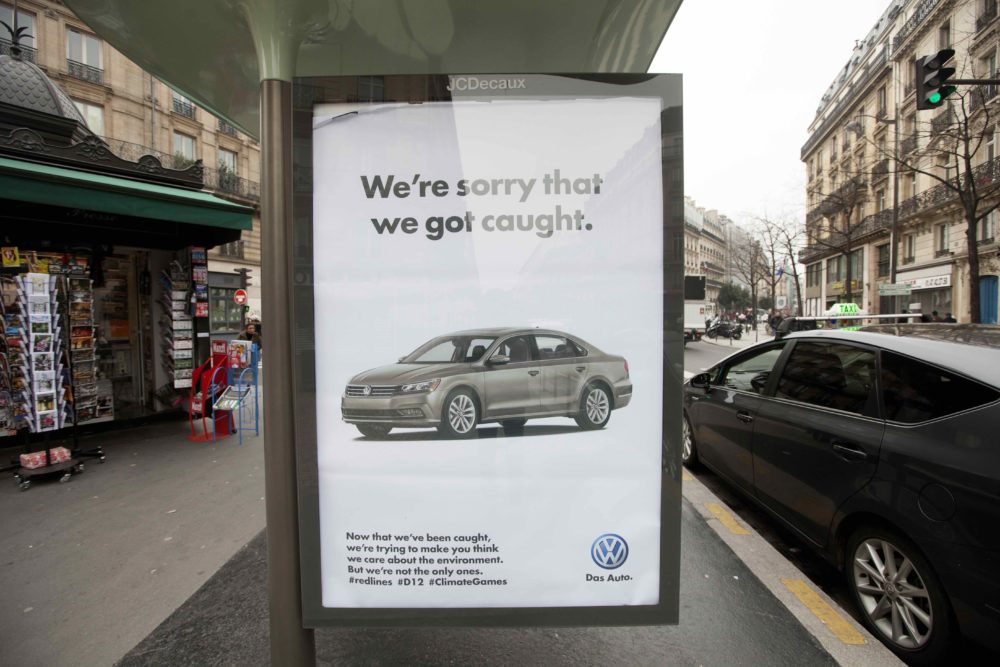

You’ll have seen subvertising popping up everywhere recently, from co-ordinated campaigns against advertising and the state to individual artists taking autonomous action, like Hogre. Campaigning groups are also using the technique to make political points, whether about the UK government’s inhumane deportation system or the lack of recognition of LGBT history.

A portmanteau of subversion and advertising, subvertising has it’s origins in the detournement practices of the Situationist International. Now A new book from Dog Section Press – Advertising Shits In Your Head – takes a look at the contemporary subvertising movement, as well as offering the reader advice on how to get involved. Below are short introductions and interviews with three subvertising groups – Public Ad Campaign, Brandalism, and Special Patrol Group – that feature in the book.

Public Ad Campaign

Jordan Seiler began subvertising at art-school. After being challenged by a teacher that he probably wouldn’t take over all of the ad spaces in a subway station for his thesis, that’s exactly what he did. His practice grew from there, as he took on more and more ambitious take-overs – including the world’s first international outdoor-ad takeover. He sees himself as more of an artist than an activist and claims he lacks traditional “political ambition”; however, he also says that he considers “good art to be activist” in and of itself.

Jordan now works with black and white geometric patterns, which – although aesthetically considered – deliberately avoid using a slick commercial advertising design aesthetic. His beautiful black and white installs are as far removed from adverts as possible, without just looking like empty spaces (which they would do if they were just black or just white). In addition to his collective projects, Jordan still does independent installs in his native New York, and around the world.

Unlike many other subvertisers, Jordan does not carry out his work anonymously, and believes it’s important that he claims ownership of his output. Starting out in the street art tradition, he called the project Public Ad Campaign as a pseudonym, but has since been more open about his identity. “It’s important to identify with your demands, to own them,” he suggests. “Rosa Parks would not have been Rosa Parks as Anonymous.”

Q: Obviously you came from an art background. Do you consider your work, these days, to be more art or activism, or both, and where are the intersections between them?

I view my work as more art, but I consider good art to be activist. So, like, things that hang pretty above your dining room table are boring to me – not really art, more design. Art has this connotation for me of ideas and issues beyond any sort of aesthetic gymnastics and self-reflexive history.

So, I think my definition of art tends to sway towards activism, or social engagement. I consider myself more of an artist than an activist. And partly because I don’t really have any issues, and I don’t have any issues that I feel strongly enough that I can demand specific outcomes for and so this, this is all sort of an attempt to just put an idea out into the world and let it grow, which I think of as an artistic act.

Brandalism

Bill Posters started his art-life as a graffiti writer, writing on roofs, trains and walls as part of a graffiti crew while at university. After becoming politicised by the Iraq War, he ended up writing his dissertation on culture jamming, referencing Levebfre, Klein and the Situationists, and says this acted as the “anti-business plan” for what became Brandalism.

The first Brandalism project in 2012 had billboards and consumerism as its target, and saw Bill recruit a friend (who is still part of the anonymous Brandalism crew) to help with the installs. Though the billboards caught the attention of much mainstream media, including a 4 minute segment for Channel 4’s Random Acts, the billboard twosome quickly realised that they were “just two people in a van”. Since then, their focus has been on empowering others to take their own actions, and every campaign since has seen more and more people involved as Brandalism has developed an ‘open source’ model to hacking public space.

Bill Posters sees the work of Brandalism and the process of replacing adverts with art – as a gift to society, an extension of the approach Joseph Beuys developed. Unlike advertising, this exchange demands nothing of the viewer, and can be viewed as a two way interaction. Internationally acclaimed artists have featured in Brandalism’s projects – Peter Kennard, Stanley Donwood, Barnbrook, Gee Vaucher, Robert Montgomery – but on the street you wouldn’t know as they’re artworks are presented anonymously.

Q: What would you like to be the outcome of your work? And has that changed over the course of the project?

The outcome of my work has changed as the project and processes involved has changed. The first project was just two people, thinking that they had something important to say – backed up by loads of academic theory and papers and just generally sound ethical understandings of what is good and healthy and important. We created the first project as an analysis and critique of corporate led, visual culture using art to articulate the issues so it was representational in nature. A good starting point but we hadn’t started to make art politically yet – in relation to Capitalism. We were making political art but some of the processes and structures involved weren’t referencing, no embodying the forms of political organising that are necessary in a participatory democracy so we weren’t making art politically in the way we wanted to. Questions around power and privilige still remained so we started to pursue and develop a model based on ‘open sourcing’ the development, and using digital networks to create communities of practice to further develop the practice.

For us the aesthetic outputs of the project are important, and are crucial to public engagement, however our project is process-led which is where the art resides and takes form in the way we organise and create with others together.

Q: How do you view your practice: as art or activism? What are the intersections?

Yeah, this question’s been going round in my head, because It is good to question what art is. At the moment I personally believe that in the current context of our time, given our current position with regards to where our society is, and the age we’re in – which is the anthropocene, where we have this physical layer in the sedimentary history of the planet now that is forever changed through human actions – I cannot see any meaningful art that is not activist in nature, that is not engaging and challenging that reality and our place with it.

I mean, there’s creativity and there’s craft, but for me… I don’t want it to be utilitarian, but I feel that creativity and resistance now are so hand in hand, or should be hand in hand, because we need them to help us move closer to some form of wider consciousness that will hopefully emerge and develop the cultures that we live in to be something more than they have been.

Special Patrol Group

Special Patrol Group (SPG) are thought to be a shadowy, militant wing of STRIKE! Magazine. Their name is a reference to the controversial and now disbanded Met police unit, notoriously responsible for the death of teacher and activist Blair Peach.

Based in London, England, they started their work by taking designs from the magazine and installing them in bus stop six-sheet spaces, London Underground ad spaces and on billboards. In 2015 they were part of Banksy’s Dismaland exhibition, where they gave demonstrations in bus stop hacking and also made their Ad Space Hack Pack available, both to visitors of the attraction and online.

More recently they’ve been installing subverts in solidarity with other campaigns – including Netpol, the Heathrow 13 environment group and Veterans for Peace. At Glastonbury 2016, they launched their international Ad Hack Manifesto, as part of a subvertising installation in Shangri La. The ad-cabinet (which was procured legally but clandestinely from Clear Channel Outdoor) has now been installed at DIY Space for London, where it is used for subvertising training sessions.

Q: What is the Special Patrol Group?

Well, it’s not really a group, for a start. It’s been many different people at different times. It’s horizontally and anonymously organised. It’s more of a tactic than an actual group, anyone can take direct action against advertising anonymously and claim it in the name of SPG. That’s both to protect people from police action, but also part of an anarchist tradition of presenting work anonymously. Oh, and it’s also a way of subconsciously reminding people that the Metropolitan Police Force are institutionally racist and can murder with impunity.

Q: Do you see your work as more art or activism?

The two are completely intertwined. But always as ‘activism’ first and never ‘art’ alone. The aesthetic is fundamental to our work but must always be shaped by political motivation. The visual image must have a function and we increasingly reject ‘art for art’s sake’. It’s not enough that the image is radical, the positioning must attack something also. That said, we might just be vandals, attacking private property out of frustration and for the fun of it. I mean, it definitely is fun.

Q: What would you like to be the outcome of your work?

We have an anarchist, anti-capitalist outlook, and we’re just trying to suggest alternatives really. When politics and art collide on the streets we can challenge the corporate capture of our public spaces and turn the language of consumerism against itself. But more broadly the intention is to activate and politicise people, to use public space, and encourage social good. We’d really like people to take their own autonomous action, for people to make and remake their urban environments and claim their right to the city.

Also the total disbandment of the Metropolitan Police Force.

Grab a copy of Advertising Shits In Your Head.

These words first appeared in an article for Huck magazine

Image credit: Protest Stencil